Writing With a Broken Tusk

Writing With a Broken Tusk began in 2006 as a blog about overlapping geographies, personal and real-world, and writing books for children. The blog name refers to the mythical pact made between the poet Vyaasa and the Hindu elephant headed god Ganesha who was his scribe during the composition of the Mahabharata. It also refers to my second published book, edited by the generous and brilliant Diantha Thorpe of Linnet Books/The Shoe String Press, published in 1996, acquired and republished by August House and still miraculously in print.

Since March, writer and former student Jen Breach has helped me manage guest posts and Process Talk pieces on this blog. They have lined up and conducted author/illustrator interviews and invited and coordinated guest posts. That support has helped me get through weeks when I’ve been in edit-copyedit-proofing mode, and it’s also introduced me to writers and books I might not have found otherwise. Our overlapping interests have led to posts for which I might not have had the time or attention-span. It’s the beauty of shared circles—Venn diagrams, anyone?

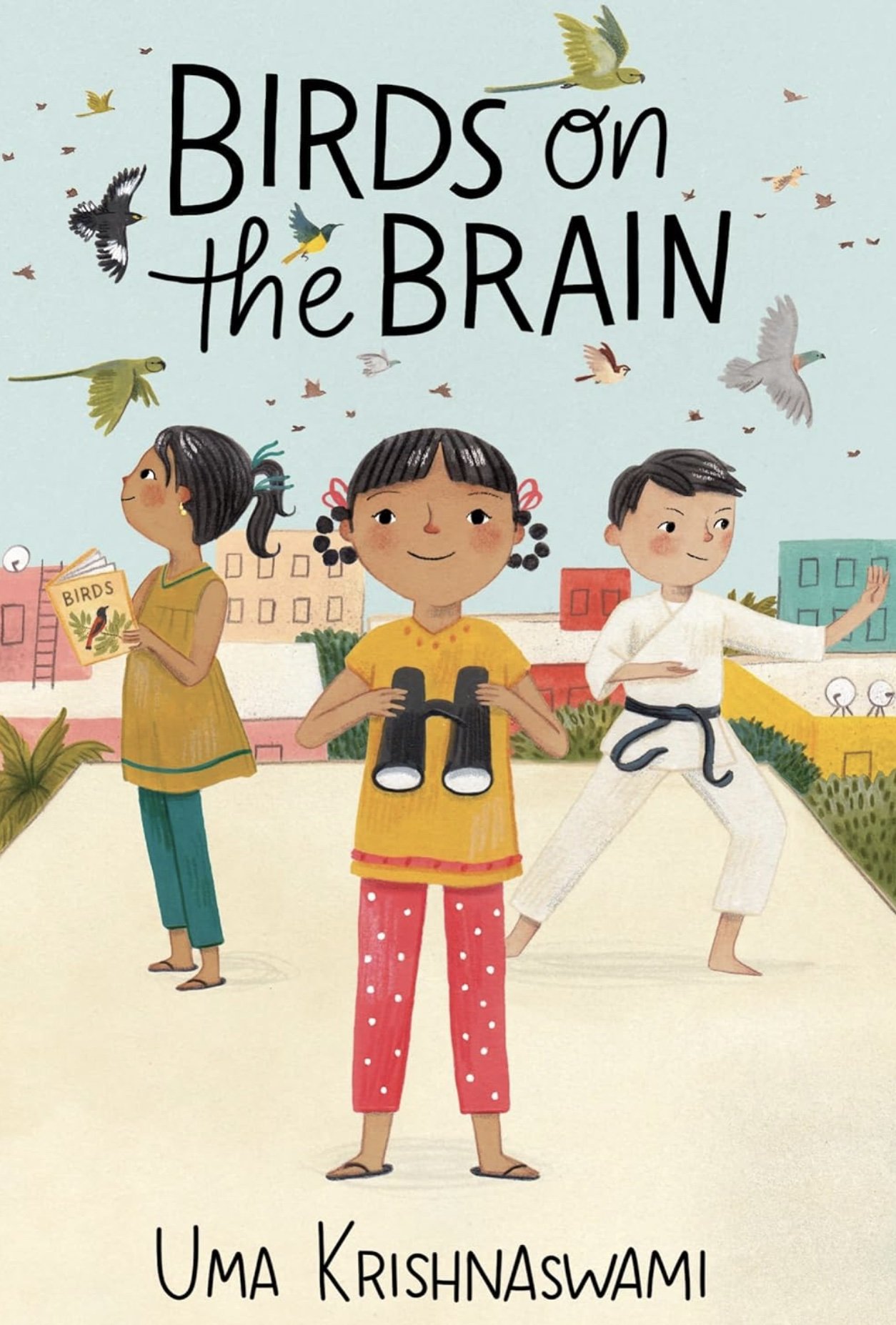

Guest Post: Letting Characters Lead the Way by Saumiya Balasubramaniam

Happy coincidence, or inspired planning? On April 2, Groundwood Books will publish two picture books set in India: my Look! Look! of which some more here and still more to come, and When I Visited Grandma by Saumiya Balasubramaniam. Since our books share a publisher and a book release date, I thought I’d ask Saumiya to write a guest post about the making of this book.

Process Talk with Jen: Martha Brockenbrough on Human and Artificial Intelligence

[Posted by Jen Breach for Writing With a Broken Tusk]

Martha Brockenbrough is a writer of very considerable brain. An example: her acknowledgements for Future Tense: How We Made Artificial Intelligence–and How it Will Change Everything (out today from Feiwel & Friends) are couched in a conversation with ChatGPT, in which Martha teaches the AI exactly how many people it takes to make a book. “‘Given all the work that goes into a book,’” she asks it, “‘and all the human beings required to do that work, do you still think [a book can be written] in six months to a year?’ ChatGPT was silent for a long time. And then this reply appeared, in red type: ‘An error occurred. If the issue persists, please contact us through our help center.’”

Meet Jen Breach

This blog began in 2006 as an exercise, a discipline, a meditation for me, a way to think out loud while I was trying to think on the page in my books for young readers. Over the years it has taken on its own trajectory and become a record of sorts—a patchwork quilt of my reflections on crossing borders of all kinds as they relate to writing and teaching. It has come to include the reflections and opinions of others who create books for children and young adults.

In 2024-25, I’ll have 4 new books out, each with its own timeline of edits, copyedits, and a series of proofs, and I am not getting any swifter. Spent years multitasking and living to the thrill of the looming deadline. Can’t do that any more. So rather than shut the blog down and retreat for months on end, I’ve decided to get help.

Why You Should Read (or Reread) Emil and the Detectives

In 1929, a German writer named Erich Kästner published a book for children titled Emil und die Detektive. An English translation was published in 1931, Emil and the Detectives. In 1934, all of Kästner’s, except Emil, were publicly burned by the Nazis and his writings were banned. Kästner stood nearby, watching his books go up in flames. Emil was burned a year later.

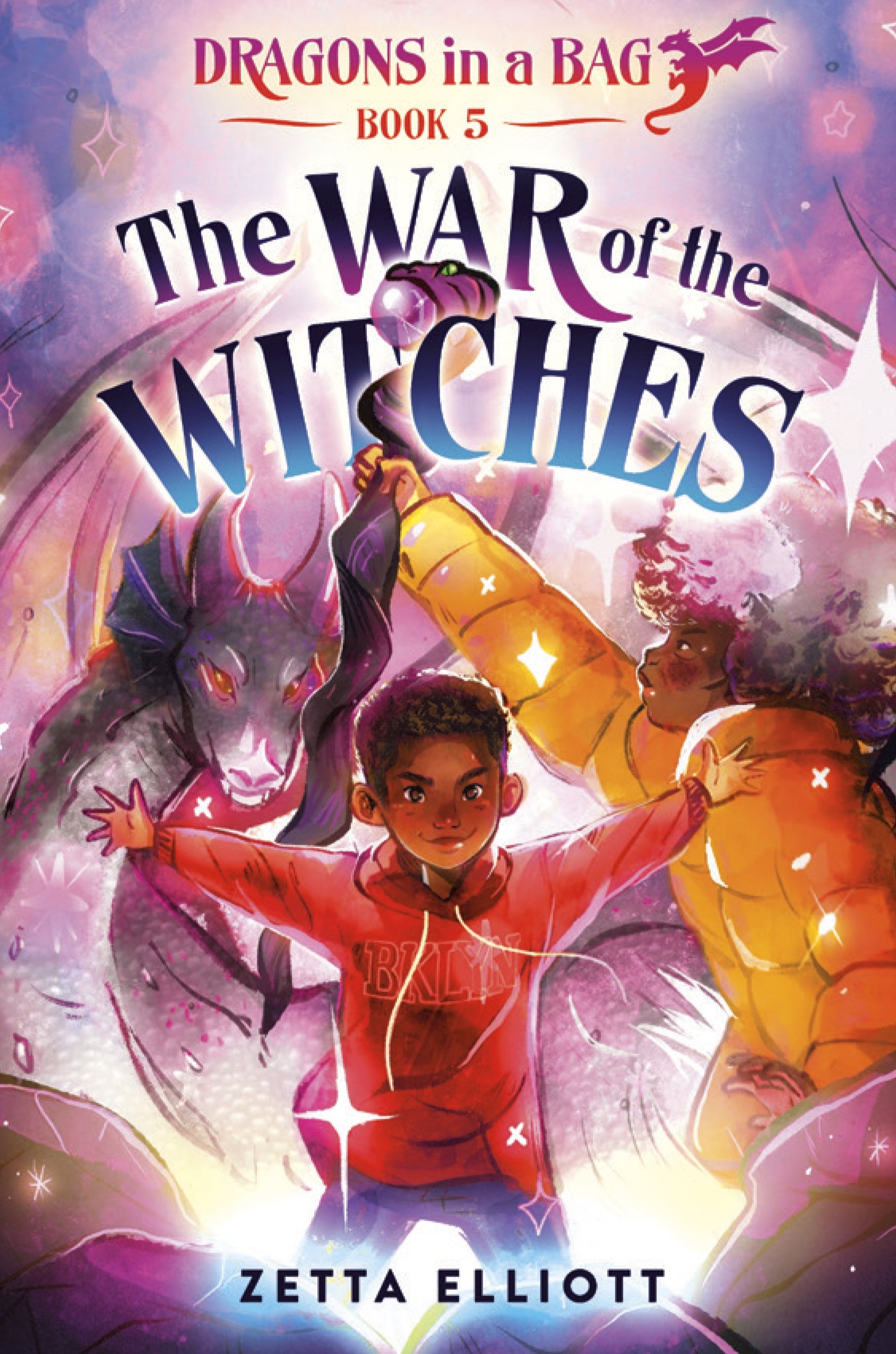

Process Talk: Zetta Elliott on Dragons in a Bag (Part 3)

For some months now, I have been email-chatting with Zetta Elliott about her Dragons in a Bag series. At one point, relative to how the deeply personal finds voice in fiction, she wrote:

In 2004 my father died and I accepted a teaching position in Djibouti. It was my first time in Africa and the job ultimately fell through; I chose to return to Toronto and moved back home with my mother.

Process Talk: Marion Dane Bauer on We, the Curious Ones

I had read Marion Dane Bauer’s books long before I met her. As a newbie on faculty at the legendary Writing for Children and Young Adults MFA program at what was then Vermont College, I was in awe of Marion and dazzled by her many accomplishments. What I have come to realize over years of residencies and conversations and lectures and all the years since, is my sheer good luck that our paths crossed in this way. Marion has a mind that melds curiosity, poetry, and a keen awareness of the young. She can write the clearest scenes I can think of and create chapter books that fool you into assuming they must have been simple to write. Whenever I had students who struggled to understand what it took to write a scene, I’d make them read Marion’s Runt or one of her ghost middle grades.

Marion also mines complex sources like no one else and extracts texts that sweep through time and evolution, mythology, the spiritual, and science. See my posts on this magnificent picture book, The Stuff of Stars.

Now there’s a companion title, We, the Curious Ones, illustrated by Mumbai artist duo and couple, Hari and Deepti.

Jacket! Draft! Trilogy!

I wrote Book Uncle and Me without a thought about who it might be for. I wrote it because the story kept scratching at the inside of my brain and wouldn't leave me alone. It was originally published by Scholastic India. I never thought I would ever write a sequel.

Only a couple of years ago, when I was doing a zoom presentation during the Covid years, a child in the audience asked, "Is there going to be a second book?” The question stayed with me, although I didn't have a coherent answer for it at the time.

Process Talk: Heather Camlot on The Prisoner and the Writer

I don’t remember where or when I first heard of The Dreyfus Affair—the wrongful conviction and imprisonment of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer attached to the French General Staff, on charges of military espionage and selling secrets to the Germans. It might have been included in one of those Reader’s Digest Condensed Books that I devoured, reading scaled-down versions of dozens of titles that I’d never have found otherwise in my childhood years in India.

I can’t remember, but at any rate, Dreyfus was found guilty of treason and sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil's Island. For more than a decade, a small group of human rights activists worked to clear his name, among them author Emile Zola. The real culprit was identified and Dreyfus was eventually pardoned.

Decades after I first heard that story, I’m talking to Heather Camlot, author of The Prisoner and the Writer, about the exchanges between Zola and Captain Dreyfus that led to Dreyfus’s eventual release.

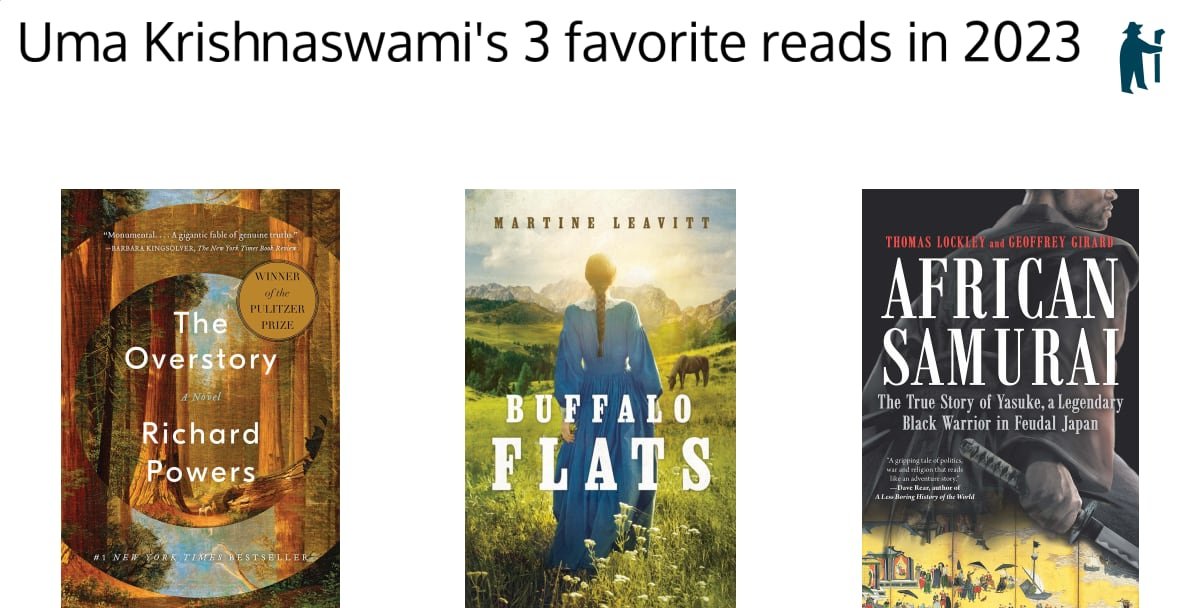

Shepherd: Best Books of 2023

Thanks to Ben Fox and his team for their tireless zeal to get books into the hands of readers. When they asked me to pick three favourite books for last year, I demurred at first—what? Only three?

Process Talk: Zetta Elliott on Dragons in a Bag (Part 2)

Here’s Part 2 of my conversation with Zetta Elliott about her Dragons in a Bag series.

[Uma] I was thrilled to see Book 2 weaving in the history of Siddi people in India. It’s a history so subject to centuries of erasure that it just made me happy to see it, particularly this way, so loving and threaded through with magic. Can you tell me more about writing this part of The Dragon Thief?

Process Talk: Zetta Elliott on Dragons in a Bag (Part 1)

Zetta Elliott has long been unafraid to address elephants in the rooms of children’s literature that others might prefer to ignore. Back in 2010, in her Horn Book article, she wrote about decolonizing the imagination:

I marvel at the girl I once was. Why would a plump, brown-skinned girl with an Afro embark on a quest to read all the books she could find by Frances Hodgson Burnett? Was I an Anglophile in training, or was my taste in books (and music, and clothes) a way of rejecting popular representations of blackness, which fit me just as poorly (if at all)? Up until grade three I started each school day by singing “God Save the Queen,” so perhaps my taste in literature was the inevitable result of Canada’s colonial legacy.

All of this really spoke to me, since these are the very elephants I’ve done my best to interrogate over the years. So I was interested when Zetta said in her 2023 Zena Sutherland lecture that “fame and visibility shape systems of recognition.” I assumed that her Dragon books have managed to hit the fame button nicely on the nose, but what I wanted to know was what made her write the first book. So I reached out to ask her.

The Cotton Wool of Daily Life

A few weeks ago, I found myself stuck at chapter 11. For some reason, in every novel I have written, chapter 11 serves up my moment of reckoning. I dash through the first 3, then the first 10 chapters in a rush of chaotic creation. By chapter 11, I’m wondering, Is there enough in this thing that is trying to be a book? Is there too much? Does the story have its own interior logic? I feel it thinning out beneath my fingers. I feel it is in danger of slipping away. That’s when I step away and read. Essays, poetry.

“This Story Starts at the Beginning of Time.”

From its beginning, this blog has been about borders—understanding them, crossing them, finding ways to think about them. The Edge of the Plain: How Borders Make and Break Our World by James Crawford examines borders through history. About the oldest known remnant of a border, a single pillar covered with Sumerian cuneiform inscriptions, Crawford says, “This story starts at the beginning of time.”

Time and Place in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese

One thing it took me awhile to get used to with audiobooks is that they flow past you like water. You can’t stop them to make notes. Well, you can, but it interrupts the flow. The library app will let me rewind and listen to passages now and then but often they’re gone before I recognize that need.

There were many passages in Abraham Verghese’s novel, which he reads himself The Covenant of Water, that I wanted not only to revisit, but also to mark up and write notes about, and more, maybe I just wanted to see them. I wanted to see how they scanned on the page.

Caveat Auctor

When John Zubrzycki’s history of Indian magic was published in 2018, Michael Dirda of The Washington Post wrote a grumpy review with a scattering of admiration. Dirda’s criticism cited typos, misspellings, garbled sentences, redundancies—in other words, slovenly editing

Here’s a grudgingly admiring snippet, the annoyance aimed at the publisher, Oxford University Press:

Oxford’s delinquency is particularly annoying because Zubrzycki, an expert on South Asian history, clearly worked hard to produce what is, despite its textual irritations, a valuable and entertaining book.

Unease and Interruption in Lincoln in the Bardo

At its opening, Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders feels disjointed, its many voices cutting in on one another, as if they’re keeping the reader from focusing on the promised tragedy and the story that has already taken flight. Then you realize it’s meant to feel this way. It operates somewhat in the way that history filters down to us in scraps of narrative from different points of view. Jangling, clashing, fighting for space.

You think, there’s a story here if I just relax and let it wash over me. Then you begin to see.

Histories No One Taught Me: the Story of Yasuke, African Samurai

African Samurai: The True Story of Yasuke, a Legendary Black Warrior in Feudal Japan by Thomas Lockley and Geoffrey Girard is a deep dive into the story of a little-known historical figure: an enslaved man from East Africa transported by the Portuguese to Japan, left behind there with a Jesuit mission. He came to be known as Yasuke, and fought alongside feudal lord Odo Nobunaga to become Japan’s first foreign-born samurai.

Laughter and Hats: Remembering Betty-Erle Rhodes

When I met Betty-Erle Rhodes, she’d just moved to northwest New Mexico. She was a storyteller. She had the kind of face that always seemed ready to break into a smile. She wore embroidered skirts and glorious hats. We served together on the board of the local arts council and met up for lunch and tea every so often. A few of my books were out in the world, but I struggled constantly with self-doubt, never knowing when the publishing faucets would run dry. Betty-Erle had been a children’s librarian and she believed passionately in the power of books and reading.

Quick Reads: In the Morning I’ll Be Gone by Adrian McKinty

I listened to the audiobook edition of In the Morning I’ll Be Gone by Adrian McKinty, book 3 of the Sean Duffy series, read by the golden-voiced Gerard Doyle.

It’s set in Belfast in the early 1980’s but close to the end, here are headlines that scream about Mrs. Gandhi’s assassination:

“Murdered by her Sikh bodyguards in retaliation for her assault on the Golden Temple. I read the reports, which went on for four pages. It was horrific stuff. There had been retaliatory massacres of Sikhs in Delhi, gun battles in the streets. “

The passage ends with a globe-shrinking sardonic aside from the narrator on the effects of British rule in India!