Process Talk: Susan Fletcher on Sea Change

Photo courtesy of Susan Fletcher

Susan Fletcher is no stranger to my bookshelf, to my circle of writer friends and colleagues, or, for that matter, to this blog. I’ve been enchanted by her Journey of the Pale Bear, by the luminous setting and endearing band of waifs in Falcon in the Glass, and by the spirited character of Marjan in Shadow Spinner. Her Dragon Chronicles (Dragon’s Milk, Flight of the Dragon Kyn, Sign of the Dove, and Ancient, Strange, and Lovely) play out over a timespan that stretches from a Welsh-inspired storyscape all the way to the thump of an egg and the life of a girl in Oregon, in a polluted present time.

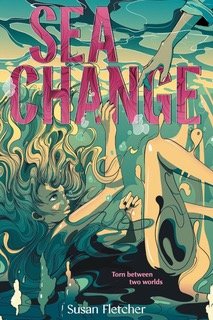

Now Susan brings us Sea Change, a reworking of the story of The Little Mermaid. It’s a YA science fiction tale of a gill-breathing girl contending with family and community and love on a climate-impacted Texas coast.

I recall with fondness my own childhood introduction to Hans Christian Andersen in a picture book, so Susan’s fracturing of this complex, beloved story sang siren-like to me. It’s my delight to chat with Susan about Sea Change.

[Uma] First things first. Susan, talk to me about the opening. The setting, the piano, the perspective, the blood! Not your typical romantic encounter, this, and no fluffy heroine here. Was this always the opening or did you arrive at it through revision?

[Susan] I actually went back and checked in the earliest draft I could find, July 2019! And that opening was in there, pretty much as it stands today. Except that the piano came later. In that early draft, I imagined that Turtle’s family used to play in a bell choir together, and Turtle finds one of the bells in the opening scene. But there’s something so tragic about a grand piano underwater. The utter ruination of such a splendid and extravagant thing. Something that says disaster in a way that a small bell could not.

Even earlier, though… I’ve had a minor obsession, for decades, about flooded cities and towns. Atlantis, for instance. And a legendary flooded Welsh village, where you can sometimes hear the sounds of the old church bells ringing. Modern cities, towns, and villages flooded to make way for hydroelectric projects. I can’t explain why I had this fixation, but I wanted to weave it into a novel, somehow, though I couldn’t figure out how until the idea for this story came to me. And so I had to get into that flooded townhouse early on and imagine what this peculiar kind of disaster might have looked like.

[Uma] You’ve built a society where the boundaries of “normality” are not predicated on race but rather on genetic modification. Can you recall how you arrived at the particular complexities of this post-climate catastrophe society?

[Susan] Years ago my daughter, Kelly, who did a lot of work in microbiology on the way to her Ph.D. in engineering, told me that amazing things were happening in the field of genetics, and that maybe I should look into it. So I did. Siddhartha Mukherjee’s book, The Gene, was a delight and a revelation. Searching my news feed every day for items about genetics, I encountered the gene-editing technique, CRISPR, and learned that a revolution in human gene editing is now well under way. At this moment, human gene editing is used mainly to cure and prevent disease. But new uses are on the way. What happens when people can edit human genes to make their own children stronger, faster, and maybe even smarter? What happens to the kids who are left behind? What happens when the inevitable mistakes are made? What happens when some people push human limits and create people who can hear as well as bats, smell as well as wolves, see as well as eagles? Or, perhaps, breathe underwater?

Humans evolved as tribal creatures, and that’s turning out to be pretty darned stubborn—and divisive. So I can’t help but fear that, with the advent of radical gene editing, the issue of race might one day be overshadowed by something that divides us even more.

[Uma] You disperse backstory, in particular Turtle’s backstory, strategically through the book. Can you talk about the choices you made that help give context without feeling as if we’re stepping too far from the story that lies ahead of Turtle?

[Susan] Weaving in exposition is so hard in speculative fiction! Not only do you have the usual job of weaving in your characters’ backstories, you have to weave in the backstory and rules of the world of the book, as well. And in the case of Sea Change, the backstory and rules of the book world are really complex.

In early drafts, I always want to tell too much, too soon. Partly because I’ve done so much work to figure it all out! I have to tell myself to hold back, hold back, hold back. Trust the reader. The reader will wait. With luck, she will be curious and keep reading in order to see the big picture, what’s really going on. She will collect the little pieces as I dole them out bit by bit. She will try to fit them together; she will trust me to give her the pieces she needs when she needs them. I’m hoping that by the time when I finally spell it all out, the reader has slotted a lot of the puzzle together already and is eager to discover the rest.

[Uma] I'm fascinated by the character of Nancy Costigan, whose research bookends the novel. Tell me how she became the documentarian of this story.

[Susan] I wanted a way to put in a little bit of information, early on, about what’s going on with the Mer. To orient the reader, give her some clues. A few quotes from a fictional book seemed to suit my purpose. So I made up a book, A Brief History of the Mer, and put quotes from it at the beginning of the various sections of Sea Change.

But after a while I began to wonder… Who wrote this (made-up) book? Do we know the author at all? And then I thought: Could the author be a character within the story? And Nancy came to mind right away. She’s really bright, and she’s stuck in a difficult position where she doesn’t have enough to do with her mind. Doesn’t have a challenge, or a way of being very useful, or even much hope for the future. Sometimes a kid like this will create some chaos, some resistance, out of boredom or just for something to do with her mind. And that’s Nancy, all over. So, making her the author of the made-up book gave me a way to hint at some hope for her future. She gets an education, a worthwhile project catches her attention, and the next thing you know she’s a historian, researching and writing books!

[Uma] In this book, you make the fantastic real but you do it by moving in very close and allowing the reader to sense a shower of finely wrought details. I’m thinking of the scene in chapter 19 where she’s in the water, going down, and we experience a deluge of sensation. By the end of it, I am convinced that I know exactly what it feels like to mouth the tastes of the ocean, to savor them—“crustacean armor, seaweed spore, jellyfish goo.” I know what it feels like to push that water through gills I do not have. What intuitions lead you to this kind of word magic?

[Susan] Years and years ago, I wrote a trilogy of fantasy novels, the Dragon Chronicles. And I know from writing about dragons that when you’re asking the reader to suspend her disbelief in things that are patently not of this Earth, you have to work extra hard to make those things seem real. One way is to lean in extra hard on sensory detail. What, specifically, would it feel like or taste like or smell like? What, specifically, is down there, in the waters of the Gulf of Mexico? In the case of gill breathing, I had to look up how that actually works. You suck in water through your mouth, and then push it out through your gills, and then… Well, obviously, I wasn’t going to actually try that. But I could close my eyes, and imagine.

[Uma] “When you’re a little kid, you can’t know if your upbringing is crazy weird. It just seems ordinary to you.” This rings so true, and it makes Turtle the voice of every child who has ever felt like an outsider. Can you talk about how you developed Turtle’s character?

[Susan] As a child, I was in the insider group, in terms of race and religion, in the places where I lived. And yet there were occasions when I felt like an outsider. My family moved across the country several times, often in the middle of the school year. Each time, I dropped into a mini-culture where I didn’t know the rules. I didn’t wear the right clothes, my hair was all wrong, I talked funny, I had no idea what music or radio stations to listen to. Most kids in the new places were nice, but a few of them made sure that I—and everybody else—knew that I didn’t fit in. Not to make too much of it, but I was to some degree wounded by those experiences. They were temporary wounds, but I didn’t forget. In each case, by the time the following school year rolled around, I was fine.

I emphatically do not want to equate my experience with the difficulty and trauma of someone who is mocked, or worse, for his religion, cultural background, sexual orientation, and/or the color of his skin. But I had that little bit of lived outsiderness to work with, and I leaned into it as I wrote.

What the Mer have going for them is that they do have a community, a tribe, a pod—a whole bunch of other kids who have gills and lungs. They band together against the inevitable slings and arrows that come zinging in their direction. So they are wounded, but they also develop a prickly defensiveness, shared humor, and solidarity, which protects them to some degree.

[Uma] This book points to our time, but indirectly, which makes it even more powerful. To what extent was writing this novel a way for you to make sense of the world we find ourselves in right now?

[Susan] I love this question. Books written outside of the author’s lifetime—historical fiction, science fiction, fantasy—often address, from a distance, the issues of the time period in which they were written. And that is certainly true of Sea Change. You’ve got global warming and sea level rise—clearly omnipresent concerns right now. Human gene editing is just getting started, with its promise of eradicating horrible diseases…and its threat of creating holy hell if implemented unwisely. So, in those cases, by imagining the future, I was definitely exploring and trying to make sense of what’s going on right now.

And there’s another way in which this was happening as I wrote. I didn’t plan it beforehand; it just arose from, I dunno, life. It’s the divisiveness and anger I’m seeing all around us, right now. It feels like we’re flying apart, and that makes me really sad. I think that’s why Turtle resists having to choose between her birth family “Normals” and her Mer pod. There are people she loves in both cultures, even though their groups are often in opposition. She longs to reach across.

[Uma] If you had to pick one thing that you'd want readers to take away from this book what would it be?

[Susan] More than anything, I’m hoping that readers will be swept up in the story. In my experience, different readers take different “messages” from the stories they love, depending, perhaps, on what they need or are ready to hear. So I just hope that readers will be swept up!

[Uma] What a vast and complex project—what helped you push through to the end?

[Susan] Well, just to say, I guess, for starters, that this is the most challenging book I ever wrote. The combination of trying to wrap my brain around as much of genetics as I needed to understand, and writing in a genre that’s pretty new to me, and dealing with a huge cast of characters, and deeply inhabiting the point of view of a fifteen-year-old girl who can breathe with gills… I did a lot of floundering (if you’ll pardon the fish pun). It took me a long time to get my arms around the whole thing and mostly wrestle it to the ground. (To mix metaphors.) Anyway, what I really want to say is that despite how crazy lost and befuddled I was at times, I love doing this thing that you and I do, Uma. The making of stories. It’s part craft, part intuition, part magic, part I-dunno-what-all. It grabbed hold of me while I was writing my first novel, lo these many years ago, and it’s fed me, excited me, expanded my view of the world, and deeply satisfied me ever since. I’m so grateful to have been able to spend my professional life this way. And I’m also grateful for the friendship and generosity of other writers, who have enriched my life beyond what I can say.

[Uma] And I am grateful for you, Susan, for the fine storytelling and the incredibly hard work that goes into everything you write.